Why the ancient Christians had a smaller (and bigger) Bible

Protestants, Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox, and the Oriental Orthodox all encompass the ethos of “mere Christianity,” an umbrella term used to categorize the nucleus of Christian doctrine essential to the four groups that qualify them, in the eyes of most, as Christians; however, none of the four groups can completely agree on what the Bible actually is.

To Protestants, the Biblical canon contains 66 books; to Catholics, seven more are required (Sirach, Wisdom, T obit, 1 Maccabees, Judith, and additional parts of Daniel and Esther). In fact, the Catholic Bible contains the account of Hanukkah whereas the Jewish Old Testament, called the Tanakh, does not. A Jewish scholar once described this phenomenon as akin to if the Jewish Bible contained the story of Christmas, but the Christian Bible did not.

Additionally, the Eastern Orthodox possess even more books and verses than their counterparts, affirming the canonicity of 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, an extra Psalm (Psalm 151) and a prayer called The Prayer of Manasseh in The Book of Chronicles. Perhaps most thought-provoking, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church views The Book of Enoch, a collection of three volumes attributed to Enoch, as canonical. Throughout its history and especially with the advent of the internet, The Book of Enoch has become the center of great interest, controversy, and speculation and was alluded to by the Apostle Paul and the authors of Jude, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter.

Clearly, not all Christians can agree upon which Bible is valid. If this dilemma seems complex enough, enter the world of ancient Christianity.

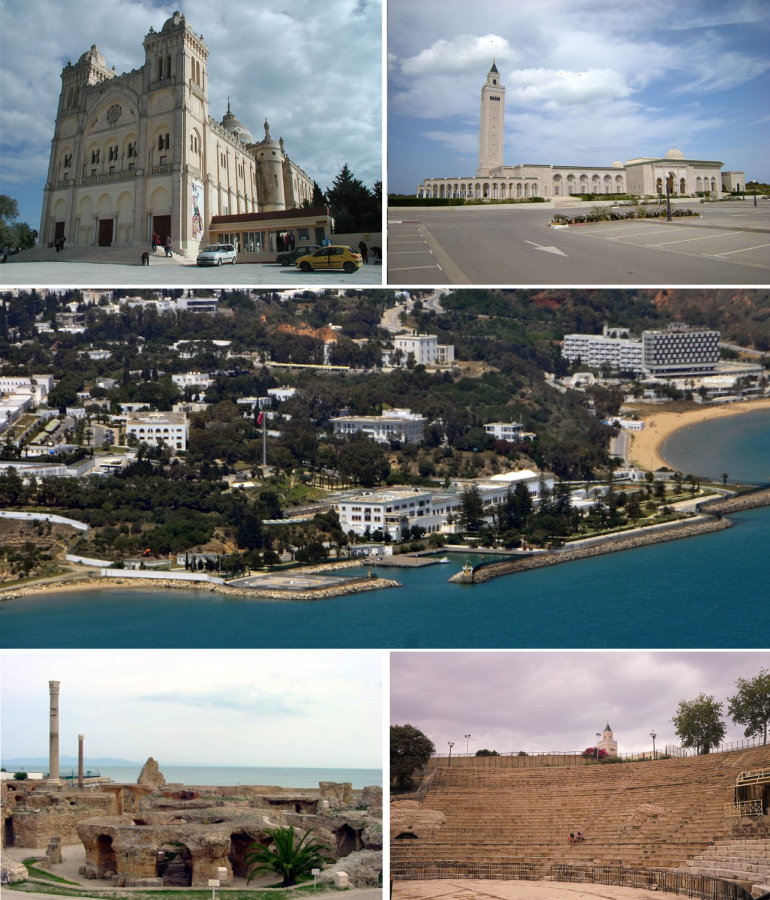

The most influential early Christian theologians, called the church fathers, can help scholars determine what the Biblical canon of the first four centuries of the Common Era looked like before the official adoption of what is now more or less the Catholic canon in the year 397 CE at the third synod of the Councils of Carthage.

Polycarp of Smyrna, (70-155 CE) a canonized saint across all denominations that venerate saints and one of the earliest Christian writers, espoused a New Testament canon similar to the 27-book New Testament accepted by all Christians today (except for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which contains more texts). Polycarp accepted 1 John and 3 John as well as The Epistle to the Hebrews, all of which are present in the Bible today, but were controversial in the world of ancient Christianity; however, Polycarp appears to reject 2 Peter and 2 John as non-canonical. This is not necessarily surprising as 2 Peter was a highly contentious text among many early Christian intellectuals such as with Origen of Alexandria (circa 185 to 253/254 CE), the great genius who served as the dean of the highly-influential Catechetical School of Alexandria after the deanship of Clement of Alexandria (circa 250 to 211-215 CE) and was posthumously declared a heretic, rejected 2 Peter as a forgery. Today, the text remains divisive among scholars and apologists of other faiths.

Irenaeus of Lyon (120/140 – 200/203 CE), also a canonized saint across all denominations that venerate saints, affirmed a larger New Testament canon. According to Irenaeus, a book called the First Epistle of Clement and The Shepherd of Hermas were both divinely inspired. The First Epistle of Clement, or 1 Clement, is possibly the oldest extant Christian epistle outside the New Testament which was likely written around the year 70 CE. In 1 Clement, Clement of Rome, a first-century Christian, writes extensively about avoiding the vices of jealousy and schism that threaten the Christians in Corinth. His letter mentions the martyrdom of Peter and Paul and strongly implies that Paul was killed in the Iberian peninsula, not Rome, where he is traditionally said to have been beheaded at the behest of Nero.

In addition to 1 Clement, Irenaeus also recognized The Shepherd of Hermas, an immensely popular text among the early Christians that was almost included in the 397 canon, as divinely inspired. This book is narrated by a prophet and former slave named Hermas, who, despite being illiterate, is showed a variety of visions by which he attains secret knowledge of divine reality, which he is told to write down; however, Irenaus appears to reject some books that all Christians today view as canonical.

Irenaeus, like Polycarp, his teacher and predecessor, who was possibly a disciple of the Apostle John, apparently rejected 2 Peter, as it was absent from his masterwork Against All Heresies, but arguably accepted the then-controversial Epistle to the Hebrews. References to 3 John, Jude, and Philemon, an epistle unanimously accepted by scholars as authentic, are also conspicuously absent from his writings.

Picture courtesy of Wikipedia

Prolific author, apologist, and theologian Tertullian of Carthage (155/160 – circa 220 CE) considered The Shepherd of Hermas to be canonical during his period as a proto-orthodox believer, but later rejected the book when he joined the highly controversial movement of Montanism, an apocalyptic and proto-Pentecostal group that was both supported and opposed by proto-orthodox bishops.

According to the fourth-century Church Father and translator Jerome, Tertullian became disillusioned with the perceived laxity of the proto-orthodox, or emerging Catholic, church and joined the Montanists due to their demanding moral codes and doctrine of the imminent end of the world, but later found the group still too lenient and left to start his own sect that survived until the fifth-century.

Despite accepting The Shepherd of Hermas as canonical, there is nothing unusual about his canon in comparison to the modern canon.

Picture courtesy of Wikipedia

Origen of Alexandria (circa 185 to 253/254 CE) and his mentor Clement of Alexandria (circa 185 to 253/254 CE), although the former becoming controversial in the later church, developed the doctrine of apokatastasis or universal salvation, based on theology extracted from The Apocalypse of Peter, The Sibylline Oracles, and The Gospel of Peter.

Picture courtesy of Wikipedia

The Apocalypse of Peter is a second-century text written from the perspective of the Apostle Peter and was likely brought on by a vision from an unnamed Christian prophet with a special devotion to the Apostle Peter. This concept of meditating, fasting, and praying until one entered an altered state and began to experience visions was common with both Jews and Christians of the first and second centuries as evident from The Greek Apocalypse of Ezra, The Apocalypse of James, and more. The aforementioned Ireaneus despised these texts and denounced them as Satanically-inspired.

The Apocalypse of Peter also influenced Clement of Alexandria and his successor to the deanship at the Catechetical School of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, to adopt the doctrine of universal salvation, known as apokatastasis, but how they went about forming this doctrine is worthy of another article entirely.

Perhaps the father of the modern Biblical canon was Athanasius of Alexandria (circa 293 – 373 CE), a zealot of trinitarianism and a staunch opponent of Arianism (the rejection of Jesus’s coequality and co-eternality with the Father) and mystical monastic traditions that prevailed in Egypt until he wrote a fictionalized biography of premier monastic Anthony the Great (251 – 356 CE) and oversaw the oppression of anyone who opposed his monastic reforms. Despite enduring exile five times, Athanasius’s vision of the belief in the Trinity as necessary for salvation absolutely without exception was finally realized in 381 at the First Council of Constantinople.

During his battle with various groups that he perceived as heretical, Athanasius reimagined the antagonists of The Book of Revelation, the canonicity of which was hotly debated throughout the second, third, and fourth centuries, as the group whose beliefs he despised. Athanasius wielded the book as a theological weapon and it was finally included in the 397 canon for reasons very similar to his own.

Clearly, the early Christians, perhaps more extreme than disputes among the Protestants, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox, disagreed on what exactly the Bible is.

https://www.catholic.com/qa/do-catholics-and-orthodox-have-the-same-bible

http://www.ntcanon.org/Origen.shtml

http://www.ntcanon.org/Tertullian.shtml

http://www.ntcanon.org/Polycarp.shtml

http://becomeorthodox.org/the-catechetical-school-of-alexandria/

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1010.htm

https://www.bible-researcher.com/carthage.html

https://madainproject.com/rylands_library_papyrus_p52

https://web.archive.org/web/20180310053222/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Origen

https://www.jpost.com/blogs/through-a-glass-darkly/the-textual-criticism-of-the-bible-408867

Pagels, Elaine H. Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in The Book of Revelation. Penguin Books, 2013.

Xavier Nazzal is a senior who serves as the Executive Online Editor for the Lion Journalism 2022 - 2023 school year. Among other things, Nazzal participates...