Think of the last couple of times you traveled out of state. For you and for many Bellarmine students and faculty, it may conjure memories of piling into a car or bus, suitcases in tow and driving to the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, or more affectionately named by many, SeaTac. Being the largest airport in Washington, SeaTac is the hub for aerial travel domestically and internationally, with over 1000 takeoffs and landings daily, transporting our friends, family and loved ones domestically and internationally for longer than most of us have been alive.

However, this scale comes at a cost not just in ticket prices or time spent in TSA lines, but in an environmental impact, affecting the communities of color, immigrant and refugee populations that surround the airport increasing rates of asthma and lung diseases, while the airport gears up to expand further by adding new facilities, providing more flights, and breaking passenger records. Though in the face of these airport titans, with seemingly endless amounts of money to keep expanding and growing, these communities on the margins, scientists, organizers, activists, and community members are making their voices heard.

But before that, how did SeaTac even get to this point?

An (Abridged) History of SeaTac

Like many, many things in the puget sound, it started in a time of war. In the early 1940s, with World War II escalating, Seattle found itself at the heart of a booming wartime aviation industry, subsidized by the Rosevelt administration. Boeing was cranking out bombers by the thousands, and existing airfields were overwhelmed. Even before Pearl Harbor, the skies were crowded, and the region needed more space.

Enter Bow Lake. Once home to rabbit farms, a frog patch, and even a mushroom farm, it was soon chosen as the future site of Seattle’s new airport. The spot was picked not for scenic views, but because it made sense: it was close to major roads, had room to grow, and perhaps most importantly was closer to Tacoma than the Eastside.

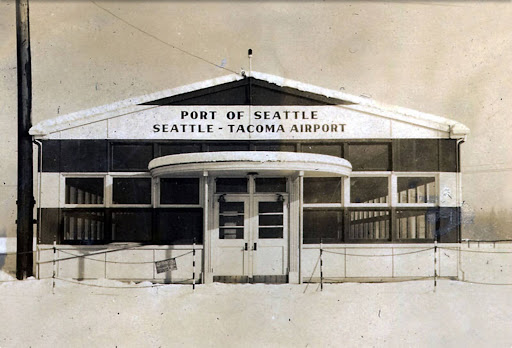

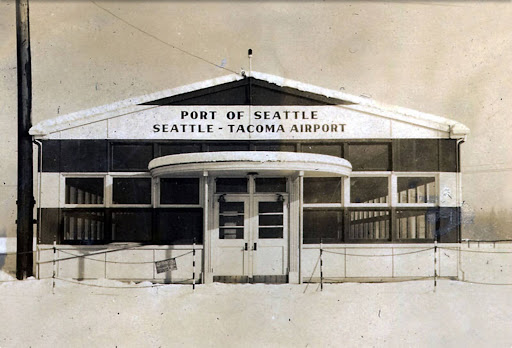

Ground broke in 1943, and though the first runway was ready by 1944, though the airport wasn’t built for tourists at this point.

By 1946, the war was over. And air travel was just getting started. SeaTac opened with little more than a barracks and by 1949, SeaTac had transformed. A sleek, modern terminal was unveiled, complete with glass-walled concourses, a barbershop, a gift shop, and even live jazz. More than 30,000 people showed up for the dedication. Then within five months, the airport was handling 1,500 passengers a day on 60 scheduled flights, and just like that, Seattle was airborne.

Which leads us to the late 90s where the Puget Sound Regional Council approve Port of Seattle’s plan to build a third runway, where the Puget Sound Regional Council approved the Port’s plan to build third runway at Sea-Tac Airport in 1996, despite mounting environmental concerns and fierce opposition from local communities, one of the most significant environmental challenges being the destruction of 17 acres of wetlands, and impacting several streams and wetlands a part of the Des Moines watershed. Many residents voiced concerns about the loss of vital ecosystems and the escalating noise pollution.

Environmental groups sued, fearing long-term ecological damage, while others questioned whether the expansion truly served the community’s best interests. Despite these objections, the Port of Seattle pressed forward, and construction began, escalating in both cost and complexity. The project, initially budgeted at $217 million, ballooned to over $1 billion by its completion in 2008, leaving many in the surrounding areas disillusioned and frustrated with the lack of meaningful concessions for the communities most affected by the airport’s growth.

This leads to now, where the port seems to have created some concerted efforts to offload their massive effects on the environment, like SAMP, or the Sustainable Airport Master Plan, which is extremely misleading.

The Port of Seattle proposes a 40% increase of passengers, triples air cargo, and doubles international flights, and despite the outcry of the near airport communities (which include Burien, Des Moines, Federal Way, Normandy Park, Renton, Sea Tac, and Takwila, this doesn’t even start to include the people who are under the flight paths but not near the airport), it’s claims that there will be little to no impact on already overburdened communities, 64% of which are people of color and 29% immigrant and refugees. But what exactly are the issues these communities are facing?

The Untold Cost of SeaTac

All airplanes put out pollutants, that’s a given cost for most if not all forms of transportation, but a study done by the department of environmental and occupational health sciences at UW found that communities around SeaTac are exposed to a ‘unique mix of air pollution associated with aircraft’. They found that communities underneath the downwind of jets are exposed to ultra fine particle, or UFP, pollution that is not covered under the clean air act and therefore isn’t measured or regulated by the EPA.

However, medical studies suggest that long term exposure to UFPs can cause cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases, and according to king county’s Community Health and Airport Operations Report Related Noise and Air Pollution, many of these near airport communities are shown to have nearly double the rates of asthma, lung disease, premature birth and high blood pressure.

UFPs are not where environmental issues stop, though. Noise pollution caused by the planes is shown to cause sleep disturbance, sleep disturbance and chronic stress as well as poor school performance around children. According to Lynda from No Added Harm, a coalition that educates on the health disparities that occur with near airport communities, “Friends and family from outside of SeaTac will visit and ask us how we [Residsidents of SeaTac] notice how loud the jet engines are, and it’s those moments where you realize that this isn’t normal.”

And when communities try to speak out about these health disparities, Lynda alleges that they are faced with barriers such as the lack of accommodation around other languages people in the community may speak, despite such a high population of refugees and immigrants and physical barriers preventing people from connecting with their community on these issues during town hall meetings. She also noted the fear many community members have now about speaking up due to the fear of being detained by ICE. Lynda and No Added Harm contend the idea that any of the economic benefits that the airport gives to the surrounding communities off set the issues they face claiming that they should never come at the cost of the well being of the community most especially the elderly , disabled, and youth who are disproportionately affected by the issues brought by the airport.

However, though many residents have voiced concerns about health impacts and environmental degradation, not all experiences are the same. Tegan Fuller, a graduating senior at Bellarmine and long-time Des Moines resident, lives just five miles from SeaTac. “Most of the time I don’t even notice the planes,” she explains. “In fact, I actually notice more when they are absent.” Her family deliberately chose the area, drawn to the community and the proximity to the airport supports her father’s career as a pilot.

For Tegan, the airport is part of everyday life, woven into the fabric of her neighborhood. “Someone in every house works for the port or an airline,” she adds. This perspective reflects a more symbiotic relationship with SeaTac, one that is common among families employed by the airport or its affiliates. Still, her experience stands in contrast to others who report adverse health effects, language barriers, and fears around civic participation.

This illustrates the complexity of SeaTac’s role: it is both an economic engine and a source of environmental burden with its impact unevenly distributed across the very communities it occupies.

So with a community that is faced with such a complex and varied problem, what is there to do? Where can we help? Especially with so much of our access to flight travel being possible because of the burdens that are shouldered by these communities. For the case of the communities that surround the airport, it starts at stopping the harm.

As students, faculty, staff, travelers, and community members, it’s time we recognize that our convenience often comes at a cost one paid by communities who have little say in decisions that deeply affect them. Amy Savage, who runs the greenhouse and leads the E3 environmental program at Bellarmine, emphasized the importance of youth engagement in shaping a more sustainable future. She says, “Bellarmine has done a great job encouraging student-led initiatives, promoting service learning, and creating spaces where students can connect their passions to real-world issues,” Savage explained, “Projects like reducing single-use plastic use, recycling, and composting are just the beginning. To grow even further, Bellarmine can deepen its commitment by increasing opportunities for student voice in decision-making and fostering partnerships with local organizations” She believes every student, regardless of whether they see themselves as an “activist,” has a role to play.

The story of SeaTac isn’t just about planes and runways; it’s ultimately about whose voices are heard, whose health is valued, and whose homes are considered expendable for the sake of progress.

Supporting organizations like No Added Harm, advocating for greater environmental transparency from the Port of Seattle, and pushing for the inclusion of all voices especially immigrants and refugees in public decision-making processes are steps we can take. Whether that means protesting, conducting some citizen science projects on concerns based on your observations, presenting to elected officials, educating others in the community, or simply acknowledging the uneven playing field, every action counts.

Because until expansion plans consider justice alongside economic growth, the airport will never truly become a place for all to come to.

Sources:

Ryan, John. “Sea-Tac Airport Says Major Expansion Will Do Little Harm. Neighbors Don’t Buy It.” KUOW, 12 Dec. 2024, https://www.kuow.org/stories/sea-tac-airport-says-major-expansion-will-do-little-harm-neighbors-don-t-buy-it.

“Sustainable Airport Master Plan (SAMP).” Port of Seattle, https://www.portseattle.org/plans/sustainable-airport-master-plan-samp.

“Seattle-Tacoma Airport Preparing for World Cup 2026.” Simple Flying, https://simpleflying.com/video/seattle-tacoma-airport-preparing-world-cup-2026/.

“SEA Airport Basics.” Port of Seattle, https://www.portseattle.org/page/sea-airport-basics.

“Sign SEPA.” Fix the Harm, https://fixtheharm.org/signsepa/.

“State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) – Environmental Review.” Washington State Department of Ecology, https://ecology.wa.gov/Regulations-Permits/SEPA/Environmental-review.

“Mapping Jet Pollution at Sea-Tac Airport.” Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment, 6 Dec. 2019, https://deohs.washington.edu/edge/blog/mapping-jet-pollution-sea-tac-airport.

“1940–1949: The Birth of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.” Port of Seattle, https://www.portseattle.org/blog/1940-1949-birth-seattle-tacoma-international-airport.